There’s an old saying, sometimes attributed to Martin Luther King Jr., sometimes attributed to Gandhi, sometimes attributed to the Bible, that goes something along the lines of “war begets war”. What does this mean? The answer is self-evident: the only, sure, way of preventing war is from not engaging in war. With death at the top of an indeterminate list of fears, war, and heart disease, top the list of causes of death and destruction. Why would any sensible person condone warfare?

If only the world operated like a game of checkers. In that case, knowing that war brings death, and peace sustains life, one reaches an obvious solution. For the certainty seeking part of our brain, simple solutions are comforting. We are all guilty of self-deception; we like overly-simplified solutions to complex problems. Metaphors, analogies, euphemisms, cliches, and axioms help us to make sense of a world that requires nuance to comprehend fully.

As heavy and discomforting as it is to admit, war is an inherent part of our humanity. War is ever, only one decision away; consciously, or not, we are innately aware of its danger. Individually, we build and maintain peaceful relations, we fight, challenge, and destroy relations, or we isolate ourselves, and put up walls to prevent relationships at all. We build, attack, defend, maintain, all with the purpose of protecting that which we care most about. Despite our best efforts, or perhaps at an inevitable point of weakness, the barbarians find their way to the gates. It is a last resort, but with peace in mind, sometimes war is necessary.

If you are reading this blog post you are likely the type of person who seeks answers to challenging questions, or you are my mom, and maybe both. What is the meaning of life? How do we achieve love and happiness? Why do good people do bad things? What brand of root beer is superior? What are the causes of war and the conditions of peace? These are some of the most important questions, and as a result they demand we answer them, and Barq’s, the correct answer is Barq’s.

Consciously or not, you seek the answer to these questions, whether or not you choose to slump over your computer and write about these issues (it’s not all it’s made out to be). In fact, I’d suggest that your answers to these questions are of existential importance. True, our beliefs are only one, rather large, component in an engine that determines our behavior. Our past experiences and knowledge, our emotions, and our judgments, all also play a role in our behavior. Even so, there is value and benefit in considering, and articulating our answers to the questions above. In doing so we can narrow the discrepancy between actual and idealized beliefs.

Take a moment to pause and jot down your answer to each one of the questions above.

Self-help guru act aside, I hope that you will reflect on these questions. I am even more hopeful that you will consider how it is that your behavior is a reflection of your beliefs. I am most hopeful that you did not land on Compliments brand Root Beer, if so do me a favor and exit this page. These concerns are of utmost importance: what we pursue in search of meaning, love, and happiness, how we respond to our inadequacies and apparent failings, whether we choose to buy our pop in glass or aluminum. But what’s war got to do with it?

War has a bad name and reasonably so. The unknown provokes anxiety even in the most assured among us. There is some amount of predictability in living. Except in the case of tragedy, we know that the sun rises, coffee can brew, food is consumed, and then sleep overtakes us. Even a deaf, blind, mute, tactileless individual still has access to their internal world. Alternatively, those caught in a deep coma may lack brain activity but their vitals can still function with medical-technological assistance. Whether or not a person in that condition still is, is a different question. (Try thought-experimenting that one Rene.) We worry about a somewhat predictable future, how much more do we fear a future beyond which no scientific instrument has returned reliable data: death. War is a precursor to death. Must we fear war?

The fear of death is implanted in our limbic system. To have reached a point when we know what a limbic system is, each one of our ancestors survived just long enough to pass along their genes. Humans are the pinnacle of a multi-billion year evolutionary process; some have described the human experience as the universe looking back at itself. Humans survived this long because each one of our ancestors managed to get some, before they kicked it. This should come as a relief and motivation for some readers – not even one of your ancestors died a virgin; probability is on your side.

A fear of death keeps us alive. Duh. In an attempt to prevent future suffering, fear spurs us to take a position of self-preservation. Fear, in this case, is functional. But is it optimal? Even while fear prevents death it produces a reactive, and ineffective response. The antithesis of fear is courage. Courage instills us with the belief that our decisions will make a positive impact. And as some philosophers have suggested “courage is a choice”. True courage sees danger, faces it, and makes choices that lead towards better outcomes. It is an act of courage to fight that which threatens peace. It is an act of courage to prepare for war.

We love to indulge in the belief that there is the possibility of a future without loss. It is a comforting imagination, but like most comforts it has the ability to prevent us from maturing. A recognition of our own inadequacies becomes unavoidable in a world where it is near impossible to avoid the evidence of wealth, status, power, aesthetic, and genetic disparities. They say that comparison is the thief of joy. Knowing this it is easy to feel bad for thinking ourselves superior, to feel bad when we think ourselves inferior, to feel bad that we allowed our mind to make that comparison at all. Yet, the status oriented beast inside all of us needs to know our position on the hierarchy.

To that beast of comparison, surrender or submission are unacceptable, it is an admittance of our inadequacy. Often, we would rather rationalize their defeat and immediately seek another line of attack, which usually leads to even greater losses. Others might hide from their pain, and in doing so stunt their ability to learn from their mistakes. An alternative to this, as defeatist and subservient as it may sound, is acquiescence and deference.

I am working with the assumption that in war and in life, mistakes precede defeat. The unrealistic part of our brains wants to tell us that we lost because the enemy is either ignorant and malicious. Yet, those most skilled in defeat take an alternative path. Case in point, post World War II, the Japanese accepted and integrated the American model in a way that was authentic to Japanese culture. As a result Japan has reaped the dividends. Those most skilled in defeat, learn.

The Japanese understood that being is holistic. They came to terms with a reality that saw the Americans win, yes with more firepower and aggression, but, concurrently, because the American ethos was more powerful, more effective. Cream rises naturally, and, in the long-run, so to the nations and individuals whose choices are most aligned with the nature of reality. Failure is never, only because of your errors, but it is your errors that are in your control. Almost certainly, if you have failed, lost, fallen short it is because you did something wrong. When one orients oneself towards the truths of reality, remains humble and as a consequence is constantly searching for ways to improve, the rewards and a victory are inevitable.

Perhaps then, one of the questions that we should add to the list of those most important is “how do we move forward at the end of a war?” It is not victory or defeat, in themselves, that decide our fate but, ultimately, it is how we respond to them. The assurance that comes through success and victory can shroud our weak spots. The pain associated with loss breeds reactivity. In either case we ought to resist our natural inclinations and strive to see things how they really are (not how we want them to be). By regularly self-accessing, correcting, and striving, we are less likely to stumble, we are less likely to allow the external enemy, or most dangerously, the internal enemy to pull us down. With this vision, all outcomes, win or lose, are a victory.

Each one of us is a warrior. We all fight for what we desire, and through a a mix of skill and fortune we earn that which our choices determine. Those who constantly readjust, reevaluate, and reconfigure their beliefs to match the outcome they desire, are more likely to receive the reward. The author of the book of Proverbs puts it like this “A prudent person sees trouble coming and ducks; a simpleton walks in blindly and is clobbered.” We fear war because we underestimate our own ability to fight and as long as we refuse to learn, the fear remains.

A special breed of disempowerment ideology suggests that winners and losers are born and not bred. The people toting these opinions claim that one earns a special privilege by birthright; the colour of one’s skin, one’s genitalia, or a the amount of silver in one’s cutlery drawer, are claimed to be deterministic. A topic for a different blog post, I’d suggest that many of those who peddle these claims are trying desperately to maintain superiority, or alternatively they wish justify their own lack of initiative. Another view is that those who have less resources, believing in themselves, are capable of far more creativity and ingenuity. The mentality of the victor is a choice, a choice to believe that against all odds one can make the best out of any situation.

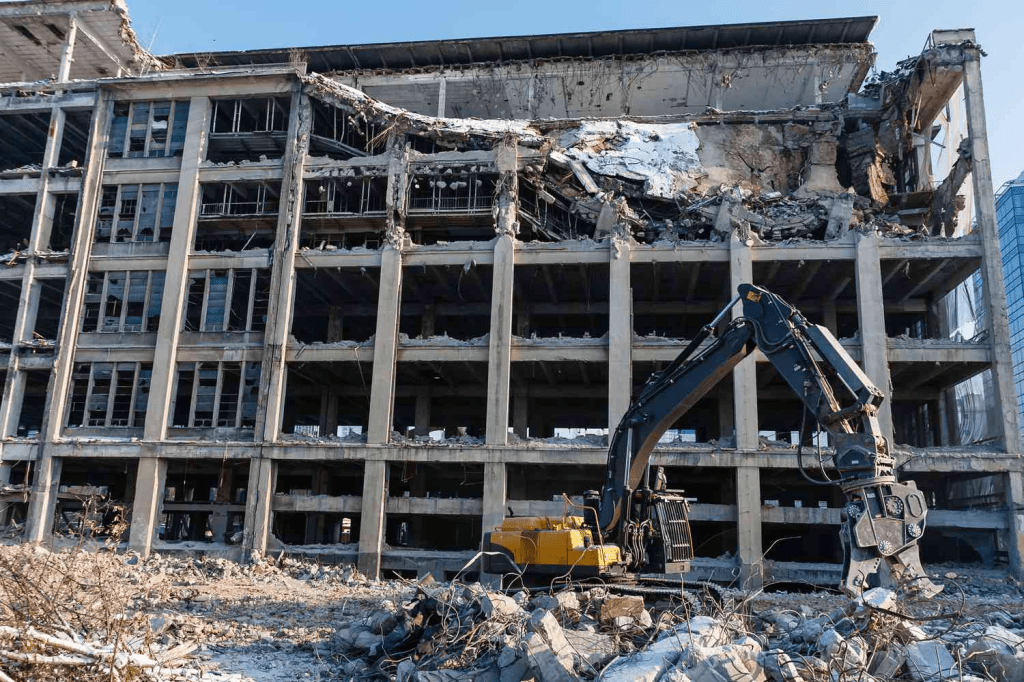

The image of a world free from war, only leads us to dismay when the inevitable occurs. The more useful perspective is to put onus back on us. It is not through imagining a better future that we earn a better future, it is through action. If we want peace we must act wisely, temperately, justly, and courageously; we must behave like a peaceful warrior. Yet, despite our best efforts, because we are imperfect, things fall apart. Expect it and prepare for victory, or pay the costs. War is not only in the literal field of battle, it can be our modus operandi for everyday life, and it should be if peace is what we desire.

Leave a comment